Ky. has 54 counties at high risk for spread of HIV and hepatitis C among IV drug users but only 6 of them have needle exchanges

Kentucky Health News

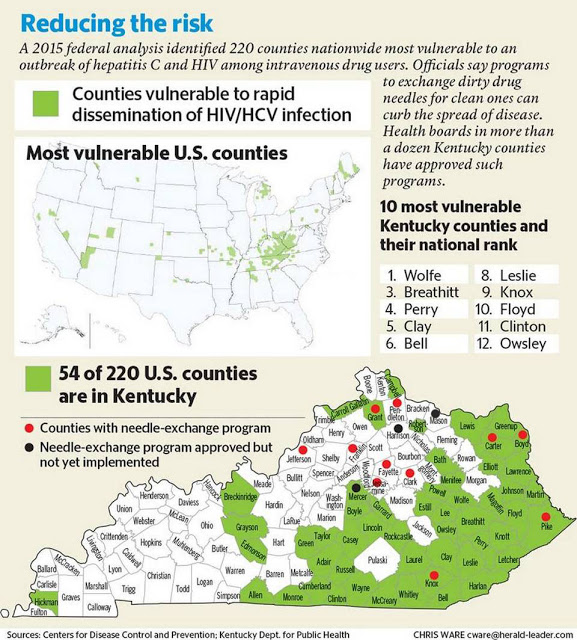

Why, if 54 of Kentucky’s 120 counties are among the nation’s most vulnerable to outbreaks of HIV and hepatitis C among intravenous drug users, do only a few of them allow users to exchange used syringes for clean one to avoid spreading the diseases?

That question was asked, implicitly, by a national expert who spoke at the 2016 Viral Hepatitis Conference in Lexington July 26.

“I think it is very interesting to compare the counties we believe are at risk, based on our modeling, and then where are prevention services, such as syringe-service programs,” said Dr. John Ward, director of the Division of Viral Hepatitis at the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “You can see there is a big disconnect, that there is a big gap in syringe service availability and other powerful prevention interventions, such as medication-assisted therapy.”

Syringe exchanges were authorized in Kentucky under a 2015 anti-heroin law and require local approval and funding. They are meant to slow the spread of HIV and hepatitis C, which are commonly spread by the sharing of needles among intravenous drug users.

So far, 14 counties have approved syringe exchanges, according to the Cabinet for Health and Family Services, with 11 of them operating. But only six (Carter, Boyd, Pike, Knox, Mercer and Grant) are in the most-vulnerable group.

A spokeswoman for the state Department of Public Health said the agency supports the exchanges and is available to provide support, share best practices, offer technical guidance, and provide information on their effectiveness and benefits.

“In addition, DPH has hosted several statewide conference calls with local health department directors to discuss setting up syringe exchange programs,” spokeswoman Beth Fisher said. “We have also coordinated several trainings for syringe-exchange staff members as well as administrators. We also work to provide education and training regarding harm reduction related to syringe use to communities.”

Dr. John T. Brooks, senior medical adviser for CDC’s Division of HIV/AIDS Prevention, pointed out the HIV outbreak that occurred in Scott County, Indiana last year, which drew national attention because of its high rates of HIV and hepatitis C.

He said Scott County isn’t that different from many rural Kentucky counties because of its high poverty and unemployment rates, low education and life expectation, lack of HIV and hepatitis C care, insufficient addiction services and no needle exchange when the outbreak began. The CDC found that 18 Kentucky counties were more vulnerable to a hepatitis C and HIV outbreak among IV drug users.

“If we don’t pay attention to history, we are doomed to repeat it at some point in the future,” Brooks said. “You want to prevent this from getting introduced and recognize it the moment it is introduced so that you can do what you can to prevent it from continuing to spread.”

Ward said multiple approaches are needed to stop the spread of hepatitis C. Using the Scott County outbreak as a model, he said a syringe-exchange program would decrease hepatitis C by 27 percent; adding medication-assisted therapy would make the decrease 41 percent; and adding a robust testing and treatment program would get it to 71 percent.

Brooks said syringe exchanges and medication-assisted therapies would reduce the potential spread of new HIV infections by 64 percent and 56 percent, respectively.

He encouraged Kentucky counties to gather their own data to determine the prevalence of IV drug use in their communities; to test people with substance-use disorders in jails and prisons, and those who frequent emergency rooms, for HIV and hepatitis C; and to create a countywide plan for a potential HIV or hepatitis C outbreak.

Referring to resistance to syringe exchanges, Wayne Crabtree of the Louisville exchange asked, “When has judgement, stigma or shaming ever made a difference in someone’s life? When did it ever change behavior? I would say never. And we in public health know it is the hand reaching out to someone in need lifting them up and making them realize their self-worth that elicits change.”

Dr. Ardis Hoven, a state infectious-disease expert, said “Stigma continues to exist everywhere around many of the issues we are discussing today and I think it is our responsibility and our challenge to begin to open up the dialogue in a way that goes to minimizing it. Because as stigma is sitting out there, we are not going to be able to get the job accomplished as well as we should.”

Hoven said establishing a syringe exchange requires local data and local allies, especially local police, who can “make or break a syringe-exchange program.”