Young diabetes coalition coordinator forms partnerships to uncover and fight the disease in five Eastern Kentucky counties

University of Kentucky

Growing up in Hazard, Brittany Martin was familiar with diabetes. Many of her older relatives had been diagnosed with the chronic condition, and her younger family members were starting to develop it as well. In a state with one of the highest rates of diabetes — 11.3 percent of adults had a diagnosis in 2014 —Martin’s family wasn’t out of the ordinary, but she found the status quo unacceptable.

Since she graduated from the University of Kentucky in 2014 with a dual degree in biology and sociology, Martin’s family history and her interest in health have converged in her current role as coordinator of the Big Sandy Diabetes Coalition, where she serves as an AmeriCorps Vista volunteer.

|

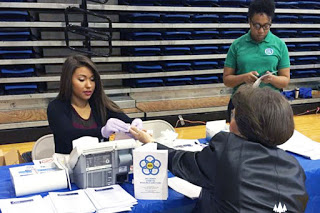

| Brittany Martin administers a diabetes screening. (UK photo) |

The coalition, based at Big Sandy Health Care in Prestonsburg, aims to improve detection, prevention and treatment of diabetes through screening and connection with local resources; it serves Floyd, Johnson, Magoffin, Martin and Pike counties, the Big Sandy Area Development District.

Diabetes is especially prevalent in the region, with 13 percent of adults diagnosed with it. In Pike County, the rate is at least 16 percent.

The rates are based on surveys that ask people if they have been diagnosed with the disease. An estimated 138,000 Kentuckians are thought to be living with undiagnosed diabetes.

As diabetes coalition coordinator, Martin juggles many responsibilities, from hosting community screenings to planning board meetings and writing a regular newsletter. It didn’t take her long to observe that irregular screenings, a lack of follow-up, and shortage of robust data inhibited diabetes prevention and care at both individual and community levels.

“We decided we wanted to set up more systematic screenings, instead of opportunistic screenings, and eventually set up a diabetes registry and keep track of participants,” Martin said.

She is now leading a project to determine whether regular community screenings and targeted follow-up can help to identify undiagnosed cases, measurably improve health, and reduce the emotional and economic burden of diabetes through connection with local resources.

“Brittany’s important work, receptivity to our input, and unparalleled enthusiasm have made her a stellar CLIK participant,” said Nancy Schoenberg, co-director of community engagement and research for the CCTS. “She is an ambassador for UK, the CCTS and CLIK, sharing her expertise and her commitment to the health of residents of the commonwealth.”

Martin, a registered phlebotomist, has personally screened 586 people since she began working with the coalition in August 2015. At each initial screening, she gathers baseline data and provides diabetes education. She then follows up with people who are diabetic or pre-diabetic to connect them with local resources and encourage them to come back for screening in six months.

Much of Martin’s work has been supported by grants and training from the University of Kentucky Center for Clinical and Translational Science, which facilitates interdisciplinary and community-engaged health research with a focus on Appalachia. A CCTS community engagement grant provided funding for a pilot study of diabetes screening at a senior living center in Pike County.

Martin, 25, has since received further funding and research training through the CCTS Community Leadership Institute of Kentucky, which aims to enhance the capacity of local leaders to address health challenges.

Through CLIK, Martin received training on evidence-based interventions, data mining for research, and data collection and analysis — essential skills to assess the impact of a project. Equipped with this additional expertise, she is now researching the effectiveness of her diabetes screening system in Martin County.

The opportunity to work in several Appalachian counties, especially Kentucky’s two easternmost, has enlightened even a native of the region about its diverse needs and challenges.

“People speak of Appalachia as a whole, but Martin County has so much less than Pike County,” she said. “Martin County doesn’t have a hospital. They have such a lack of access to care. They have one grocery store. It was very hard for me to find the resources to give them.”

Depending on the month, Martin hosts up to 10 community screenings across the five counties served by Big Sandy Health Care.

The results alarm her. “It’s actually kind of scary. Roughly 24 percent of people are pre-diabetic and 25 percent are diabetic. That’s roughly half of my sample in the red zone,” she said.

Martin sees particular challenges for individuals who face multiple health issues and dire socioeconomic circumstances.

“Sometimes we’ll go do screenings in the homeless shelter. Imagine being homeless and diabetic. Sometimes people are also recovering from addiction. Really, can you imagine being homeless and diabetic and recovering from an addiction?”

At some of the community screenings, people have been surprised to learn that they’re diabetic or at immediate risk. In a screening at Big Sandy Community and Technical College, she said, many students “learned that they had pre-diabetes, and they were in their early 20s. It was scary for them. One person was diabetic and didn’t know it. At all ages we’ve screened, there’s been at least one person who’s said ‘Oh my god, I didn’t know, I didn’t know the signs.’”

However, the data she has gathered encourages her about the potential impact of systematic community screening with targeted follow-up.

Her initial screening study in Pike County found that 50 percent of people who received follow-up information and returned for their six-month screening had lower A1C levels, the essential measurement for a diagnosis of diabetes.

Martin’s demonstrated success has also yielded nearly $20,000 in outside funding to pay for community screenings and upcoming educational classes. The Anthem, Aetna and Passport health plans have provided a total of $11,000 in sponsorships for screenings. It costs about $7 to screen one person.

Martin also recently received a $9,000 grant from Marshall University in West Virginia to support diabetes education classes in Big Sandy communities, with “gentle yoga” exercises for their clients in order to increase movement and activity, especially for individuals who are wheelchair-bound or have trouble exercising.

“There are a lot of positive health effects of gentle yoga,” she said. “We work with the aging population, and as they age we want to keep them moving. Safe, slow movements, even if someone is wheelchair-bound, can help keep away chronic effects of things like diabetes.”

Martin is developing yet another partnership to integrate retinopathy eye screenings at some community-outreach events. Over the course of nearly 600 diabetes screenings, Martin observed the a great need for eye care, and engaged both UK and the new Kentucky College of Optometry at the University of Pikeville to provide retinopathy screenings at some of her events.

When Martin isn’t busy with her full-time (and mostly unpaid) work as the diabetes coalition coordinator, she works at least 30 hours a week as a waitress. She is also studying for the Medical College Admission Test and the Optometry Admission Test, with plans to apply to medical and/or optometry school at Pikeville. Her ultimate goal is to become a practicing physician in a rural community.

She has a demanding portfolio of responsibilities, and says she sleeps about five hours a night but doesn’t tire of her work: “I’m right where I’m supposed to be.”