Study of oral health in Ky. shows progress and challenges, reminds us of connections between oral health and overall health

Kentucky Health News

More Kentuckians than ever have access to dental care because of Medicaid eligibility for dental insurance, and the state has made some gains in oral health, but finding a dentist can still be a problem, especially in rural Kentucky. And even though children on Medicaid have dental insurance, more than half of them don’t get any dental care.

Those are among the findings of a study on the oral health of Kentucky by researchers at the State University of New York at Albany‘s Center for Health Workforce Studies. It also points up the connections between oral health and overall health.

The study noted that under federal health reform, more than 425,000 Kentuckians, mostly adults, gained dental insurance through expansion of Medicaid to households with incomes up to 138 percent of the federal poverty level.

“Kentucky’s support for an adult dental benefit is huge,” Margaret Langelier, project director for the study, said in an interview. “When you have significant oral disease, it can impact your overall health in major, major ways.”

She went on to say that including adult dental benefits in Medicaid makes for a small part of the budget, but is often something that lawmakers cut out, which is a mistake.

“What they don’t understand is that these adults are still going to show up, but with a much greater progression of the disease and likely in the emergency department,” Langelier said. “So you (end up) paying for it through your health insurance.”

|

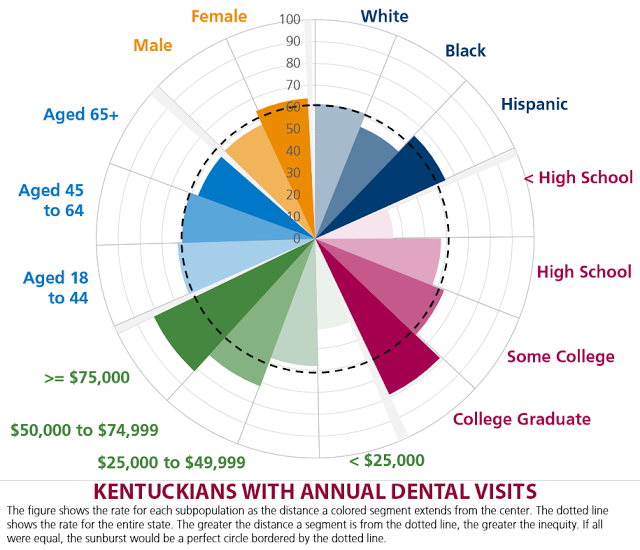

| Graphic adapted from America’s Health Rankings Spotlight: Prevention report |

The study found that 100,000 more Medicaid-eligible Kentuckians got an oral health service in 2014 than in 2013. But because many of them had multiple cavities and complicated oral-health issues, there is now a clearer need for more general and specialty dentists, both of which are hard to find in rural Kentucky, especially in eastern and western parts of the state.

In 2014, only half of Kentucky’s 22 federally qualified health centers provided dental services directly to patients, with most dental services provided by private practice dentists. And while the report found that about 40 percent of general dentists in the state provided at least one oral health service to a Medicaid patient, most of them do not participate in a “meaningful” way.

|

| Graphics are from the report; click on them for larger versions. |

The report found that “in 24 of the 120 counties, mostly in Eastern and Western Kentucky, there were fewer than 1.7 dentists per 10,000 population. There was no dentist in four counties, only one dentist in 13 counties and only two dentists in 12 counties.”

“Although the oral-health workforce in Kentucky appears to be adequate on a per-population basis, it is not evenly distributed compared to the population of the state,” Langelier told the House Health and Welfare committee Feb. 25.

The report also found that the poorest and least educated Kentuckians who live in rural areas have the highest rates of cavities, gum disease and oral cancer. “Oral health disparities in Kentucky are similar to its health disparities in the state,” Langelier said.

A separate Pew Charitable Trusts report found that in 2014 fewer than 25 percent of high-need Kentucky schools had tooth-sealant programs. The Healthy People 2010 Sealant goal is for more than 75 percent of these schools to have these programs. Dental sealants are clear plastic coatings that are applied to permanent molars to prevent cavities and school based sealant programs are proven to reduce cavities by 60 percent over five years, says the report.

Langelier told the committee that Kentucky has “made notable efforts to address oral health disparities in the state,” including: expanding Medicaid and choosing to include a dental benefit; expanding the roles of dental hygienists; implementing several programs to encourage dentist to practice in Appalachian Kentucky; and its addition of fluoride to its community water sources. In addition, she said, many regional and local initiatives work to improve the oral health of Kentuckians.

“It is widely held that there is no single solution to address all oral-health access barriers. It is also thought that oral-health service delivery must be designed to accommodate the needs of the specific local population that is undeserved; thus local solutions are preferred,” Langelier said. “However, local programs can only succeed if state payment, insurance, and workforce policy support local innovation in oral-health service delivery.”

The report recommends continuing support for an adult dental benefit in Medicaid; further utilizing federally qualified health centers to integrate primary care and oral health care needs; increasing Kentucky school-based oral health services; looking at a team based approach model that includes dental therapists; and to look at removing some of the existing barriers on dental hygienists.

The study was funded in part by The Pew Charitable Trusts. Click here to view the public hearing on the report held on the Senate Floor Feb. 25