Study: health warnings on sugary drinks make a difference; 3 states seek legislation to add them; beverage lobby pushes back

Kentucky Health News

Health warning labels on sugary beverages, like those found on tobacco products, could make parents less likely to buy them for their children, according to a study from the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania.

“Regardless of the specific wording, results show that adding health warning labels to sugary-sweetened beverages may be an important and impactful way to educate parents about the potential health risks associated with regular consumption of these beverages, and encourage them to make fewer of these purchases,” Christina Roberto, lead author of the study, said in the news release. “The findings are in line with similar studies conducted on the effects of warning labels on tobacco products, which have been shown to increase consumer knowledge of health risks related to tobacco use, and encourage smoking cessation.”

|

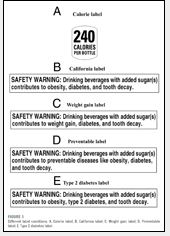

| Warning labels used in the study |

The online study, published Jan. 14 in the journal Pediatrics, included about 2,400 demographically and educationally diverse parents of six to 11 year olds. The online survey tested the effects of five different warning labels about the potential health effects of sugary beverage intake, including labels about calories, weight gain, obesity, diabetes and tooth decay.

The study found that 40 percent of participating parents said they would choose a sugar-sweetened beverage for their child after viewing a warning label, compared to 60 percent of participants who saw no labels on the beverages, and 53 percent of parents who only saw the calorie label. There was no significant buying difference between the groups seeing the calorie-only label and no label, says the report.

The research found that the specific words on the warning label didn’t make a difference in the parent’s purchasing choice, but the presence of the label did, says the report.

Soft drinks and juices marketed for children have as many as seven teaspoons of sugar per 6.5 ounces, which is nearly twice the recommended daily serving for that age group, says the report. Lead author Roberto noted that more than half of children (66 percent) under the age of 11 drink sugary-sweetened beverages on a daily basis.

|

| Graph: USDA Dietary Guidelines 2015-20 |

The Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health documents that sugary beverages “are a major contributor” to childhood obesity, a real problem in Kentucky which is first in high school obesity rates (18 percent); eighth for 10- to-17- year olds (19.7 percent) and sixth for children ages 2 to 4 from low-income families (15.5 percent), according to the “State of Obesity” report. The Kaiser Family Foundation reports that 35.7 percent of children ages 10-17 in Kentucky are either overweight or obese.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture recently decreased its recommended daily amount of added sugar by 5 percentage points, now recommending added sugar be limited to 10 percent or less of calories per day, Kimberly Leonard reports for U.S. News & World Report. The USDA Dietary Guideline report notes that almost half (47 percent) of all added sugars consumed in the U.S. is from sugar-sweetened beverages.

BJC HealthCare in St. Louis offers specific guidelines about the amount of sugar children should consume.

- Preschoolers averaging 1,200 to 1,400 calories per day should limit added sugar to about 4 teaspoons (16 grams) per day.

- Children ages 4 to 8 who average 1,600 calories per day should limit added sugar to about 3 teaspoons (12 grams) a day. To fit in all the nutritional requirements for this age group, there are fewer calories available for added sugar.

- Pre-teen and teens averaging 1,800 to 2,000 calories per day should not have more than 5 to 8 teaspoons (20 to 32 grams) of added sugar per day.

NPR reports that while no city or state has been able to pass a law to add health warnings to sugary beverages, “California, New York and Baltimore all have legislation in the works requiring these labels on sugary drinks.”

Leana Wen, Baltimore’s health commissioner, told NPR that the beverage industry is pushing back hard in Baltimore, lobbying legislators to reject the warning label policy and using fear tactics with the small businesses, telling them they will be hurt by this law.

In addition, ,”Legislation in Congress to tax sugar and high-fructose corn syrup failed to advance last year, and a few years ago a court overturned a ban on jumbo-sized sodas in New York City. Last summer the beverage industry sued San Francisco over a law that required health warning labels on sugary drinks and that prohibited ads of them on city property, saying the law violated the First Amendment,” Leonard writes for the U.S. News & World Report.

HealthDay reports that the American Beverage Association reviewed the study and issued this statement: “Consumers want factual information to help make informed choices that are right for them, and America’s beverage companies already provide clear calorie labels on the front of our products. A warning label that suggests beverages are a unique driver of complex conditions such as diabetes and obesity is inaccurate and misleading. Even the researchers acknowledge that people could simply buy other foods with sugar that are unlabeled.” The organization added: “With our Balance Calories Initiative, we are working toward a common goal of reducing beverage calories in the American diet.”