Gov.-elect Bevin repeats vow to end Kynect; he and state Senate President Stivers say Medicaid expansion will look like Indiana’s

Kentucky Health News

FRANKFORT, Ky. – From a Republican nomination won by only 83 votes to an unexpected 84,764-vote election margin, Matt Bevin will be Kentucky’s next governor, and that means the way Kentucky has embraced the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act is about to change.

Under the federal health-reform law, Gov. Steve Beshear did two big things: He expanded the Medicaid program for the poor to Kentuckians in households earning up to 138 percent of the federal poverty level; and he created Kynect, an online insurance exchange where Kentuckians above that level can buy private insurance with federal subsidies.

About 500,000 Kentuckians have coverage through Kynect, 400,000 of them on Medicaid, and Kentucky’s uninsured rate has dropped from 20.4 percent to 9 percent, the largest decrease of any state.

As a candidate, Bevin said Kentucky simply can’t afford to have so many people on the Medicaid rolls and that he plans to apply for federal waivers to create a revised program that is affordable and requires its clients to have some “skin in the game” thorough premiums, co-payments, deductibles or health savings accounts.

He has also said he would dismantle Kynect, which has been cited as a national model, saying it is unnecessary because a federal exchange is available. He can do that because the exchange was established by executive order and can be removed by executive order, but it won’t be immediate.

“The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services expects at least one year’s notice for states that want to terminate their health insurance exchanges and transfer those duties to the federal exchange,” John Cheves reports for the Lexington Herald-Leader. Also, repealing or modifying the Medicaid program “could take months of negotiations with the federal government,” Cheves writes. Here’s a look at each issue:

Kynect

“It is a redundancy that we as taxpayers in this state are paying for twice,” Bevin said in his first post-election press conference Friday.

Kynect is not funded by taxes but by a 1 percent assessment on all health-insurance policies sold in the state; presumably, most if not all of the purchasers are also taxpayers. The legislature enacted the fee more than 20 years ago to create a pool to insure high-risk people, a pool that the reform law made unnecessary. Beshear’s executive order re-purposed it.

The federal exchange is financed by a 3.5 percent fee on policies sold through it. So, the fee for Kentuckians buying policies through an exchange would go up, but it would no longer be charged on non-exchange policies.

Kentucky established Kynect with $283 million in federal funding. Vendors have estimated the cost to dismantle Kynect’s information technology alone is $23 million, and Kynect Director Carrie Banahan told Kentucky Health News in August that they expect the total cost of decommissioning it to “be significantly higher.” She also said some insurers might not migrate to the federal exchange.

Jennifer Tolbert, director of state health reform at the Kaiser Family Foundation, told Cheves that “It doesn’t make a lot of sense” to dismatle Kynect, which is “considered something of a model,” not only because it would be disruptive, but because it would mean “a significant amount of tax dollars invested here that essentially would just be scrapped,”

The day after the election, state Senate President Robert Stivers, R-Manchester, tried to connect the cost of Kynect to the failed Kentucky Health Cooperative, a non-profit insurer created and financed under the reform law. Its 51,000 policyholders will have to find new insurance for 2016.

“If you don’t have people buying those policies then you can’t fund the mechanism to get the policy,” Stivers said. Reminded that the former co-op clients have other insurers available on Kynect, he said, “We are hearing some of those are getting ready to pull out . . . because we understand they are owed millions of dollars that haven’t been paid.”

That is incorrect, state Cabinet for Health and Family Services spokeswoman Jill Midkiff told Kentucky Health News: “No insurer offering insurance products on Kynect plans to withdraw. To the contrary, they are actively participating in open enrollment,” which began Nov. 1.

When Associated Press Correspondent Adam Beam started to pose a question by referring to “the popularity of Kynect,” which has been seen in polls, Stivers became combative. “Who told you that it was great? The doctors? The hospitals? No, they don’t.”

However, during a panel discussion on these topics at the Friedell Committee for Health annual meeting Oct. 25, Bill Wagner, executive director of the Family Health Centers of Louisville, said that Kynectors, federally paid employees who help those who are unfamiliar with health insurance navigate Kynect, often “end up becoming case managers” for their patients even after they have chosen their insurance, helping them with things like finding providers who accept Medicaid, helping them with their health literacy, and helping them understand how to maintain eligibility.

A shift to the federal exchange would cause Kentucky to lose 75 percent of its funding for Kynectors, who are now in every county, Wagner said, He said this should be an important consideration when deciding whether to abandon Kynect, which is officially the Kentucky Health Benefit Exchange.

“Having the boots on the ground from the Kynectors, having the close working relationship with the Kentucky Health Benefit Exchange, I think has really helped us provide more ongoing care and coordinated case management around insurance, so I worry about that if that were to change,” Wagner said.

|

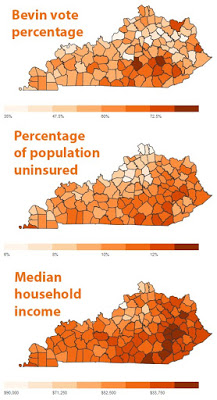

| Maps suggest reasons why Republicans don’t want to abolish the Medicaid expansion, as Gov.-elect Matt Bevin first said he would. |

Medicaid expansion

A pre-election Bluegrass Poll found that 54 percent of registered voters in Kentucky wanted to keep the Medicaid expansion, while 24 percent said they wanted the next governor to reverse it. The rest were undecided. Among those who said they would vote for Bevin, 27 percent supported the expansion.

The federal government is paying the full cost of the expansion through next year. In 2017, the state would pay 5 percent, rising in annual steps to the law’s limit of 10 percent in 2020.

Bevin said during his primary campaign that he would abolish the Medicaid expansion immediately, but in July he began saying that he would seek federal waivers to revise it, looking to states like Indiana as an example. The day before, Stivers said the legislature would decide the fate of the expansion and mentioned Indiana as a model.

Bevin told Joe Arnold of WHAS-TV Friday, “I am going to do what Indiana is doing well now.”

A state-funded study by Deloitte Consulting says the expansion will pay for itself through 2020 by generating health care jobs and tax revenue. Bevin has called the study “nonsense,” and Stivers said likewise Wednesday: “That and my roll of toilet paper could be used for the same thing.”

Stivers said Sen. Ralph Alvarado, R-Winchester, had talked to staffers for Indiana’s Republican legislative leaders about the state’s plan.

Indiana offers four plans based on income, frailty and premium payments. It requires most people to pay a varying premium and co-pay amount, has wellness and preventive-care incentives, and has provisions to remove those who fall behind on their premiums, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation.

Stivers called the Indiana plan “a framework to work from,” and noted several things that could be included in Kentucky’s plan, such allowing providers to help develop a system to set reimbursement rates, graduated premiums, penalties for bad conduct, incentives to modify bad habits, and graduated co-pays to assure beneficiaries have “skin in the game.”

“We think we can develop a plan that will not expose us to $400 million of cost, but still provide health insurance and health care for those individuals.” Stivers said, when asked if those currently covered by the Medicaid expansion would continue to have coverage. “It is a different mechanism, but it still covers the same group of people.”

Rowland also said the process takes time, noting that Utah has been seeking a waiver for two years. She suggested that Bevin’s incoming administration should consider the value of federal funds that cover 100 percent of the expansion until 2017.

Bevin “has also suggested that he would be able to keep the current enrollees on the expanded program but block out new recipients,” notes Tierney Sneed of Talking Points Memo DC. But Sara Rosenbaum, a professor of health policy at George Washington University, “called the idea that he could cap or block new

enrollees a total nonstarter” for the federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.

Also, “CMS has been relatively conservative in not granting wide scale

modifications to the program under the waivers,” Caroline Pearson, vice president of Avalere Health, an independent consulting firm, told Sneed. “There’s a

bit of political rhetoric here where the Republican governors are able

to hold up the waivers as an indication that they got a custom solution,

but it’s not having as dramatic of an effect as they are asserting.”

Under a 1966 law, the state’s policy is to maximize federal funding for Medicaid, and the Democratic-controlled state House might not go along with legislation to repeal that law. If the law remains in place, “Advocates say any move to leave federal dollars untapped would likely lead to a lawsuit,” Paul Demko reports for Politico.

Generally, health-reform advocates say waiver programs discourage people from using their benefits, meaning they may not get the care they need. “The main concern is that whatever is proposed would include more barriers to access,” Emily Beauregard, executive director of Kentucky Voices for Health, told The Courier-Journal. “None of us really understand what Bevin is proposing or how that’s going to look. That’s where we’re all holding our breath.”